We were on secondary roads headed down to Nice when I saw the sign…small and low to the ground, easily overlooked, as they sometimes are in France — as if they don’t want to be too open about their treasures. It said Châteauneuf-du-Pape with an arrow indicating left. A little burst of joy, a bubbling of excitement when I saw the name of my favorite wine. Back then I didn’t know much about wine, still not so much. I just knew what I liked, and also had no idea there was a village by the same name. We veered off immediately.

A few kilometers from our destination, we saw another unobtrusive sign. It merely said Vin. We slowed down. Peering down the long dirt driveway, we didn’t see anything that looked like an operation. We did see a house and what looked like a large barn with cultivated fields beyond that. Well, why not?

When we got close, an elderly man, unmistakably French, emerged from the house and walked over to the car. He invited us to the barn, full of his own brand. What I remember most was his offer to taste a 1969 Châteauneuf-du-Pape, what a good year it was. There was no doubt. It was something quite special. We treated ourselves to a couple of bottles of the 1969 and filled the rest of the box with those from 1976. From there, we continued on to the village and had a thoroughly pleasant 3-hour lunch.

Then there was the time driving in circles in the Rheinpfalz of Germany. We had directions written out by a friend that looked more like an indistinct treasure map, siting landmarks but no village or street names. We finally pulled up to a house, in a row with other houses and grape vines growing up the hill. There must have been some distinguishing mark about that one causing us to stop there, but no sign. My memory is foggy now. I just remember our determination to find this place since it was described so effusively by the friend who gave us the map, and our hesitation wondering if we were in the right place. But just as the friend said, a robust German woman opened the front door at our knock and heartily waved us in. She led us down to the basement, a relatively small room with large wine casks stacked two high. Elsewhere was a small table for tasting with chairs, a worktable with a labeling machine and bottles in various stages of readiness for filling and corking. She explained their process for winemaking and turned on the spigot of those casks whose contents were ready for consuming, and filled our glasses. We spent a lovely hour or so with her. She was quite entertaining…and the wine sublime.

These remembrances are from the 1980s when already these small wineries — vignerons who not only grow their own grapes in the natural way, doing the vigorous work required by hand, with distinct knowledge of their land, and also practicing the alchemy to produce fine wines — were falling by the wayside. Corporations were taking over, as with everything else, where no one is connected to the process all the way through and may not have such an investment.

There is a French term increasingly used with some food and especially in wine circles: terroir coming from terre, meaning earth or land. Terroir has to do with the microclimate of a specific region — potentially merely a parcel of land — along with the soil type — down to the microorganisms — interacting with the surrounding landscape, farming and processing methods that produce the final result…and character. An individual personality.

Such wineries do still exist, those with vignerons who embrace the philosophy and practices of terroir. But not all can claim to be natural wineries, the grapes grown organically, not even a spritz of pesticide defiling the plants, all done in the old way by hand.

During my 2018 program in Provence we were to experience a marked contrast. We first stopped by one of the large commercial wineries for a tasting. The wine was good, and most of us bought a bottle or so for later. But none of us made a connection to the place or the tasting room host who did little to engage us. The performance was perfunctory. We were in and out. I have little memory of it except what I’ve relayed. Our next visit was another matter.

We followed a road just outside the tiny village of Sannes in the Luberon to find Les Tuiles Bleues. There is quite the romantic story attached to the name, The Blue Tiles, that I promise to tell you a little later. Les Tuiles Bleues is a natural winery sharing the 30 acres with the house, barn, other buildings and large wooded area. There are 6 acres where table grapes are grown and another 6 for the wine grapes. It’s important to note the woods were left as is, not just to look nice, but to provide oxygenation to the area.

Céline Laforest greeted us in a friendly manner and invited us on a tour. This is a family business. But right away there’s a strong sense that it’s always been a labor of love about preserving a way of life. First, we noticed the house, so typically Provençal and the unusual name. And now the story where the romance comes in…

Photo: CarlaWoody.

In the 1970s, Raymond Laforest, Céline’s father, decided he’d had it with the corporate life. His dream was to have a place where he could grow grapes organically, make wine and leave a legacy for his offspring. Raymond and his wife Chantal made the leap, and Les Tuiles Bleues was founded in 1979. As is often the case, things were tough getting it all off the ground. It can be hard in those circumstances to keep your spirits up. But when things were the most challenging Raymond would break into an upbeat, happy song, Tu Verras by Claude Nougaro, reassuring Chantal…

Ah, you’ll see, you’ll see,

Everything will start again, you’ll see, you’ll see,

Love, that’s what it’s made for…

You’ll have her, your house with blue tiles…

And I will fall asleep…

The task done, laying against you…

Complete lyrics in English here.

The tricky times didn’t end back then. From year to year, there’s the risk of too much rain, not enough…all the considerations of farming, especially for those who do so naturally. But in very good years all aligns to produce stellar wines. Céline suggested we take a look at the vines. The dogs, Grenache and Lune, led the way. She lamented that they had a bad year for the vines but still managed to produce some good wine.

Photo: Carla Woody.

We continued our tour of the winemaking areas and then on to taste the results from the grapes: Grenache, Syrah, Sauvignon and Ugni Blanc. I loved having the resident cats —Banane, Bambou and Rouflette — adding to the ambience of the rustic tasting room. Of course, Grenache and Lune followed us in as well, everyone harmonious.

Well, the wine! How do I describe it? Delectable. I experienced something quite unusual. At least, I’ve never had wine generate this effect before. I took a sip of the Syrah and my palate came alive. In the next moment…my Third Eye popped open. It was truly a visceral response, and I pronounced it aloud.

Photo: Jo Elliott.

I asked some of the travelers for their input, and comparison between the two wineries if they wished.

Patricia Potts: Les Tuiles Bleues felt more natural and intimate. I loved the way the animals lived in harmony. It was a reflection of the real world. Not perfectly groomed like the other winery but perfectly imperfect. I felt the indwelling spirit there.

Share Gilbert: The winery belonged to her father… to pass his love of the earth and passion of making wine to his daughter…[It] was reflected in the wine. The flavors were pure, unadulterated and delicious. The farm felt comfortable and welcoming.

Jo Elliott: Les Tuiles Bleues had a feeling of family, animals and easiness, as opposed to the far more structured and orderly feeling of the other vineyard with its formal medieval gardens. It was this feeling of being a family business and the fact that the wines were totally natural and organic that I liked.

Photo: Patricia Potts.

Our final delight was the detour we took on our way to the van. Over in the barnyard we met the geese and watched Céline feed grapes to Sidonie, Adélaïde and Amélie. They talked a lot.

Photo: Patricia Potts.

We all bought wine but none of it made its way into our suitcases home. For my part, I wish they were right around the corner. But it gives me a good excuse to return…as I will in May 2020 sponsoring another spiritual travel journey in Southern France.

Photo: Jo Elliott.

Les Tuiles Bleues is a treasure. Such vignerons magnifiques are increasingly harder to find. It’s all the sweat and love that only those living within the spirit of the land, giving great care and attention, who can produce the kind of alchemy responsible for popping open my Third Eye. I’m convinced of that and its personality.

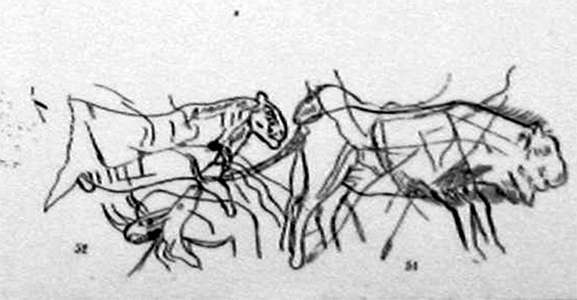

Herzog managed to produce a film that gives a visceral sense of another such hallowed space. Contained in the Chauvet site, home to cave bears, also rest antiquities – indeed lineage bearers, all that remains from the perceptions and sacred expressions of Paleolithic artists.

Herzog managed to produce a film that gives a visceral sense of another such hallowed space. Contained in the Chauvet site, home to cave bears, also rest antiquities – indeed lineage bearers, all that remains from the perceptions and sacred expressions of Paleolithic artists.