Written in collaboration with Tat Apab’yan Tew.

In February, I traveled to southern Guatemala with Maya Daykeeper Apab’yan Tew to put the final touches on the spiritual travel program we would lead in that region and Chiapas, Mexico in January 2019. When we stopped at Lake Atitlan for several days, I made sure to revisit La Galeria in Panajachel. I retained fond memories from twelve years before when my friend Will Crim and I stumbled upon the place while wandering the streets of Pana.

Vintage. ©2006 Carla Woody.

We were first attracted by the vintage Mercedes planted in the garden, and then became enchanted after entering the gallery. While making our way around the exhibition, a spare man engaged us about the artwork and offered us an expresso. We took him up on his offer and got to hear Thomas Schäfer Cuz’ stories about his mother, German-Guatemalan bohemian artist Nan Cuz, for hours. We were even invited into the inner sanctum to view his grandfather’s collection of Maya folk art. I was fascinated. This time was much the same, but we also met Sabine Völcker, Thomas’ wife, who was equally as hospitable.

This article could go in any number of directions. For now I’m going to focus on the artwork and background of Rosa Elena Curruchich ⎯ and why such works are important. In the main gallery, there was a grouping of Naïve art that caught my eye. At first glance, these miniature paintings looked simple. But beyond their style became complex, quite detailed, and there was a narrative to each one. Only that grouping was up for display at that point.

We returned a couple of days later, invited by Thomas and Sabine when they would start cataloging the entire collection. They had received boxes upon boxes of the tiny paintings to be sold on behalf of the family of a collector, possibly Anna Paddington, who had recently passed.

Rosa Elena Curruchich was the first female painter in San Juan Comalpa, a highlands town known for its artists. Her grandfather, Kaqchikel painter Andrés Curruchich, started the tradition of oil painting there in the 1930s documenting celebrations, ceremonies and lifeways. Rosa Elena followed in his footsteps. Based on her grandfather’s teachings, the subject matter explains the detail of the pieces. The more you look, the more is revealed.

But most of Rosa Elena’s are just 4”x4” or 6”x6” – none larger. Why so small? Here is the story she told her benefactor, as it was passed on to Sabine and Thomas. She was married to a prominent, authoritarian husband who forbade her to paint. So she would sneak off to paint in secrecy and limited the sizes to what she could slip into her pocket to hide. Then she would make trips to the old capitol Antigua Guatemala and try to sell them in the market. After she sold the first one to the collector, this woman became almost her sole buyer.

Another story told by Rosa Elena that I uncovered through research said after she got her first exhibition in Guatemala City, the male painters in San Juan Comalpa were jealous. She received threats and fled to Chimaltenango, about 10 miles away, to live.

The common theme being oppression by men. Sabine had already told me the story about Rosa Elena’s husband may be questionable, told in the hopes of increasing sales. The same is said of the second story. It’s called survival.

The important thing though is what Rosa Elena Curruchich and all those who followed her grandfather have done. Through their artwork, they’re documenting ways of life that are precious, many threatened. I’m a fan of narrative art. In the true sense of artistry, they are preserving what’s important. A meaningful story, an emotion, ordinary things that have a deeper meaning.

It was quite exciting to me to go into the inner sanctum of La Galeria that day Apab’yan and I were invited back. There all laid out on two tables, side by side, were about 60 or more of Rosa Elena’s works. Several boxes were still unpacked, totally about 200 in all.

As Apab’yan examined them, he began sorting the pieces into an order…each ceremony as they fell according to the calendar. It was remarkable, really. Others he separated out having to do with daily activities. I ended up purchasing 3 pieces depicting ceremonies, and wished it could have been all that fell around the calendar. Below you will see them with Apab’yan’s explanations. He told me the ones I chose depict ceremonies that are nearly gone.

This painting is showing a private celebration inside the cofradia house. In here we can see a woman and man making an offering to the patron saint. There is incense and food offerings as payment. The patron saint image is dressed as a full high-ranking member in the cofradia hierarchy. Inside the house there are the special objects to perform ceremony and celebration: a big drum, incense burners, paintings, old textiles. Cofradia members are holders of ancient ways of Maya spirituality, beyond the image of a western cult. There is always a nawal, or spirit, related to some aspect of nature.

Once again we are inside the cofradia house. In here we can see the healing of a baby. By burning specified dried herbs and exposing the baby eyes and breath to the incense burner, she or he is going to recover. We call this awas, meaning secret or taboo. It is hidden ancient knowledge preserved by cofradia members. This practice is becoming extinct except in the far away mountains where elders from a direct Maya background continue to keep a huge quantity of spiritual and medicine knowledge.

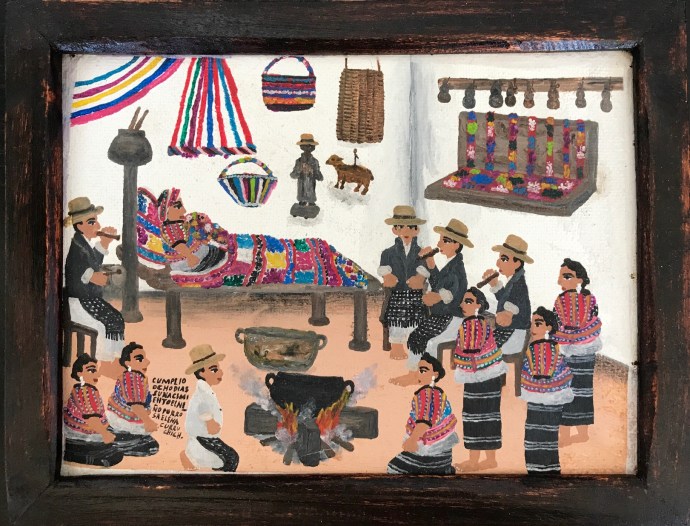

This is a celebration. There is fiesta and dance, food is prepared and musicians playing chirimia flute instruments.

Thomas told me directly this was a very important ritual done if a baby reached the age of 8 days. Infant mortality is high. This ceremony reinforced the health of the baby, who you can see laying on top of the mother, and that it would live to be an adult. The next marker was at 3 months, I believe.

This work is Rosa Elena’s legacy. Not only her own but that of her people. She passed too young at 46 in 2005, complications of diabetes.

We will be making another visit to La Galeria in January 2019, and I’m looking forward to it.

Beebe Bahrami, a cultural anthropologist and travel writer, is one of those people, too. Through happenstance, she found herself in Sarlat-la-Canéda in the Dordogne region of southwestern France. Her times there produced Café Oc ⎯an intimate love story rather than a travel book. She takes us on an unexpected spiritual journey, as she returns to Sarlat through the seasons, over a year’s time. What I spoke of in my life, she found in that medieval town and surrounding earth.

Beebe Bahrami, a cultural anthropologist and travel writer, is one of those people, too. Through happenstance, she found herself in Sarlat-la-Canéda in the Dordogne region of southwestern France. Her times there produced Café Oc ⎯an intimate love story rather than a travel book. She takes us on an unexpected spiritual journey, as she returns to Sarlat through the seasons, over a year’s time. What I spoke of in my life, she found in that medieval town and surrounding earth.

The white-haired server smiled at me in recognition after raising his eyebrows. He probably didn’t see visitors return much. But I was back at Trattoria Cribari on Piazza Santo Spirito, a little more than a hole in the wall, because I learned that not all bruschetta and gelato are created equal. Plus, it was around the corner from the airbnb place I’d rented–perfect for my needs–and they didn’t mind how long I stayed tucked just inside the open doorway watching the human world go by outside. Something of an education, a pastime I’d forgotten I enjoy.

The white-haired server smiled at me in recognition after raising his eyebrows. He probably didn’t see visitors return much. But I was back at Trattoria Cribari on Piazza Santo Spirito, a little more than a hole in the wall, because I learned that not all bruschetta and gelato are created equal. Plus, it was around the corner from the airbnb place I’d rented–perfect for my needs–and they didn’t mind how long I stayed tucked just inside the open doorway watching the human world go by outside. Something of an education, a pastime I’d forgotten I enjoy.

I love the work I do, a destiny of sorts that fell into my lap over time. I find there’s reciprocal value in it. I can’t imagine I’ll ever turn away. But. And. It requires a lot of energy. Sometimes a pause is required. Rather than leaving The Pause to chance, I made a commitment that I’d set aside time–and make it special–on an annual basis. A time when I had no responsibilities to anyone but myself. A time to rejuvenate. To experience something new or revisit something beloved. To read. To walk. To write. To learn. To create. To meditate. To talk to strangers or be silent with my own musings. To do things I love. In the past I’ve taken the mini-pause, sporadically–a camping trip here, a short road trip there as I could squeeze it in. Oh, I do all those things in my daily life I listed above–but not without interruption.

I love the work I do, a destiny of sorts that fell into my lap over time. I find there’s reciprocal value in it. I can’t imagine I’ll ever turn away. But. And. It requires a lot of energy. Sometimes a pause is required. Rather than leaving The Pause to chance, I made a commitment that I’d set aside time–and make it special–on an annual basis. A time when I had no responsibilities to anyone but myself. A time to rejuvenate. To experience something new or revisit something beloved. To read. To walk. To write. To learn. To create. To meditate. To talk to strangers or be silent with my own musings. To do things I love. In the past I’ve taken the mini-pause, sporadically–a camping trip here, a short road trip there as I could squeeze it in. Oh, I do all those things in my daily life I listed above–but not without interruption.

This year it’s Italy. This is my last night in Florence. I’ve wandered the streets, churches, museums and gardens for four days. I’ve appreciated the architecture, sense of history, the locals, the visitors. The bustle is sometimes a bit much for me, and being on top of my neighbors… I’m not used to it, living out in the boonies in solitude as I do much of the time. But the live piano music coming through a window as I walked down the street and the saxophone just next door have stirred something in me.

This year it’s Italy. This is my last night in Florence. I’ve wandered the streets, churches, museums and gardens for four days. I’ve appreciated the architecture, sense of history, the locals, the visitors. The bustle is sometimes a bit much for me, and being on top of my neighbors… I’m not used to it, living out in the boonies in solitude as I do much of the time. But the live piano music coming through a window as I walked down the street and the saxophone just next door have stirred something in me.

There was the clever double entendre: A Tale for the Time Being. We’re all Time Beings for the time being. And it’s a novel that involves time, how we experience it, the ways it warps. But you don’t realize it until you’re well into the novel. It’s subtle until firmly anchored.

There was the clever double entendre: A Tale for the Time Being. We’re all Time Beings for the time being. And it’s a novel that involves time, how we experience it, the ways it warps. But you don’t realize it until you’re well into the novel. It’s subtle until firmly anchored.